For the past 2 years, I've been working on my new game, Lamplight City. The elevator pitch I've come up with is "a detective game where it's okay to fail," but what does that mean exactly?

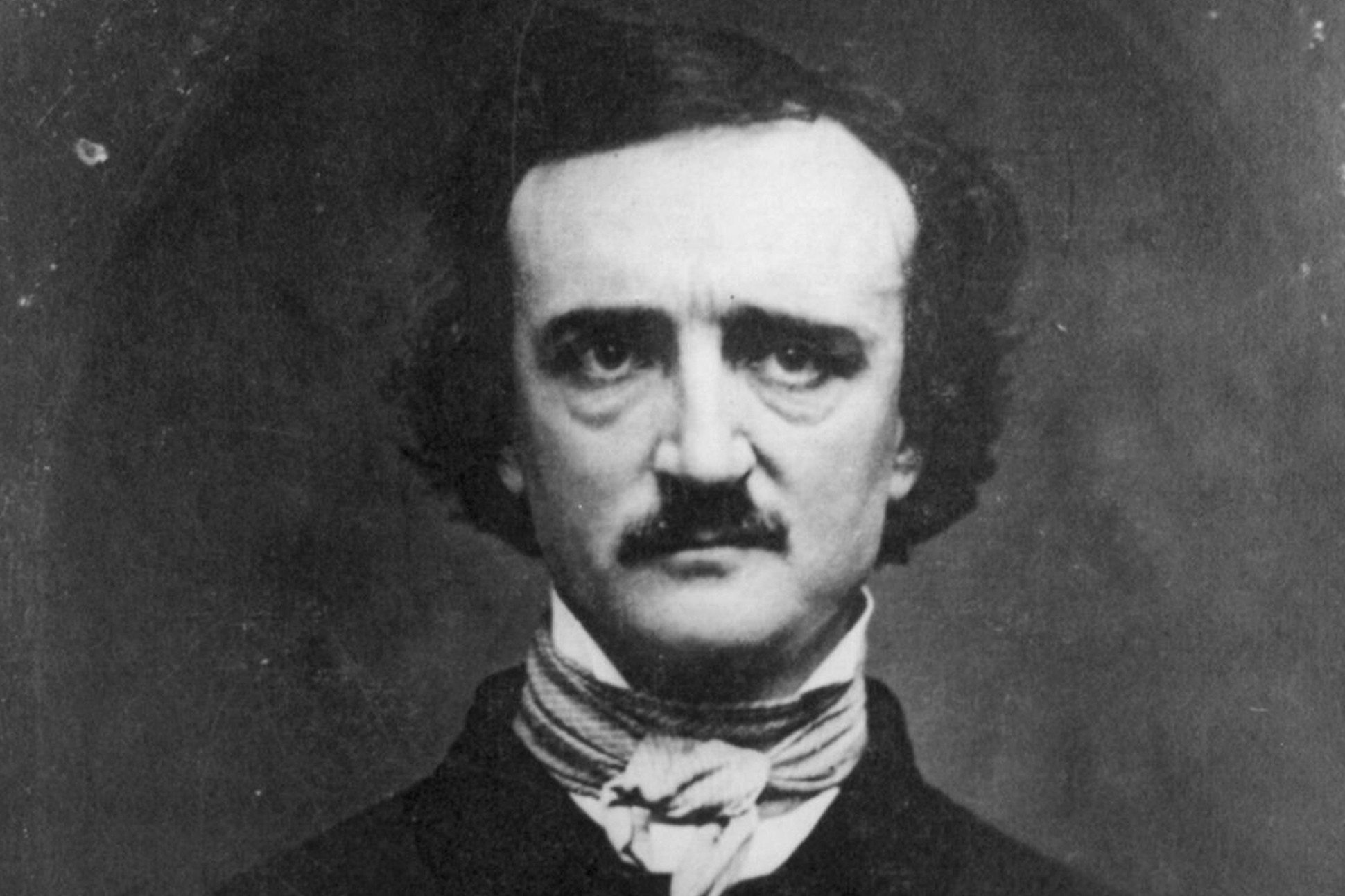

Lamplight City is a detective adventure set in an alternate steampunk-ish “Victorian” past (Since it’s alternate history, that’s why “Victorian” is in quotes) The game is divided up into 5 cases, but features one overarching narrative. Each case features multiple suspects, false leads, moral choices, and lasting consequences, and the general atmosphere and tone of the game is inspired by the works of Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens.

In Lamplight City, you play as a former detective turned private investigator named Miles Fordham, whose partner Bill is killed at the start of the game. Miles begins hearing Bill’s voice in his head, and slowly begins losing his grip on sanity. He is convinced that the only way to get rid of the voice and let his partner move on is to find the person responsible for Bill’s death, although he has no real leads, and also feels guilty and blames himself. Miles keeps himself distracted and hopes to find some link to Bill’s killer by taking on other cases, which make up the bulk of the gameplay. Each case has different leads to follow and different potential suspects. It’s your job as the player to do some actual detective work and figure out which of the leads are useful, which are red herrings, and who actually did it. In some cases you might be called upon to make moral decisions and determine if the person who actually did it deserves to be punished for their crime.

The main thing I wanted to explore and experiment with in Lamplight City was figuring out how to make a detective game with multiple solutions and paths where failure was an option, but also still an enjoyable gameplay experience. I noticed that in most games of this type, you always arrive at the correct solution, no matter what. You’re not allowed to be wrong, and a lot of the time the game will go to incredible lengths to make sure you win.

Two examples of note are L.A. Noire and Sherlock Holmes: Crimes and Punishments. Both games have a multi-case structure with an overarching storyline. In Crimes and Punishments, each case has several suspects to pick from, and it’s possible to pick incorrectly. In L.A. Noire, some cases also present multiple suspects, but only on one or two occasions does the game actually allow you a choice of who to accuse.

However, neither of these games ever allow you to get things completely wrong. If Sherlock picks the wrong suspect, the game moves on as if nothing happens, the only consequence being he gets an angry letter from a relative of the accused. Since he is Sherlock, he isn’t really allowed to fail. If a witness is called out on a lie and you pick the wrong option, you simply get to try again.

The same thing happens in L.A. Noire. In addition to that, if you follow a lead and the game has you do something like tail a suspect or begin a key interrogation, you are given infinite chances to do so. Yes, you get a game over state if they get away or you fail the interrogation, but the game picks up at the start of the sequence and won’t proceed until you complete that particular part of the investigation. Most of the interrogations are meaningless, and the game proceeds towards the right solution even if you get every single question wrong.

What I wanted to do was present situations where it was possible to have real consequences. If you make an NPC angry, they won’t talk to you any more. Fail to convince them of something, and you won’t get infinite chances. Miss a clue and lose access to a location where that clue is, you’re out of luck investigating that lead.

So, how do you make this fun? There were two simple solutions I felt were important.

The first was making investigations non-linear, so any lead could be followed or completed at any time. This is something both L.A. Noire and Sherlock Holmes do to an extent, and as a standard principle of adventure game design, it’s usually guaranteed to keep the player having fun, especially in an investigation. If you get stuck during one path, an entirely different option is available for you to investigate.

The second was having some choices made in early cases come back to haunt you. Rather than just receiving an angry letter from someone wrongly accused, I felt it would be more interesting to have a reactive world.

For example, if you’re speaking with the leader of a group of writers, and you decide to taunt her, she’ll get upset and throw you out, then refuse to answer the door, which will close off the ability to continue down this path during the first case. However, her group might come up again as a lead in a later case. If you’ve made her upset, she’ll refuse to speak with you, closing off that lead.

If you accuse the wrong suspect in the second case, you might run into her angry husband later while investigating a lead pertinent to that case, and he’ll throw you out of his place of business and deny you that lead...assuming you spoke to him in the previous case so he knows who you are. So there’s a bit of flexibility in exactly how bad you can screw things up. There are also little details like newspaper headlines and stories about the cases you solve changing based on your results.

The most important issue I wanted to overcome was what happened when a dead end was reached. In early adventure games, even up to the mid-90s, there was a design trope which has come to be lovingly named “Dead Man Walking.” This is used to describe a situation in which the player character is not allowed to proceed in the game, usually because they haven’t picked up an item, or have used it incorrectly (for example, being allowed to eat a pie which is needed to solve a puzzle later on) The game won’t let the player backtrack to pick up the item, or allow them to receive the item again, thus creating an unwinnable dead man walking situation. My idea was to take this design trope, but re-purpose it so that while it is possible to get yourself into a dead end situation, it won’t make the game impossible to continue.

As for how to communicate this idea to the player, since Miles hears his dead partner’s voice, Bill acts as the game’s second person narrator, and so it was easy to have him be able to chime in and indicate that all leads are closed off. Reporting back to your police contact then gives you the option to declare the case unsolved, which moves the story along, although failing to solve too many cases will change elements of the story and have a negative effect on Miles’s self-confidence and mental well-being.

As players, we’ve been conditioned to accept that playing a game means we always have to win, and that “winning” means getting everything completely right and being an amazing superhuman. Even though playing as a super detective might be great escapist fantasy for the player, I believe that there’s a real possibility for disconnect between player and player character when the game pushes them to be smarter than you are, and not when you’re on equal footing.

It’s a much more rewarding feeling when YOU solved the case, rather than when Sherlock Holmes wasn’t allowed to fail the case.

Lamplight City will be released later this year. You can wishlist it on Steam currently.

Lamplight City will be released later this year. You can wishlist it on Steam currently.